Austin’s Transportation Future: What Will It Look Like in 2033?

A bike ride down Airport Boulevard protected from traffic. A train traveling over 200 miles per hour from Austin to Dallas. A car driving down I-35 with nobody in it. A college student taking the light rail from the Drag to Downtown for a night out. From simplistic to futuristic, the next decade of transportation projects figures to dramatically reshape how we get around in Austin.

“If we could blink our eyes and Charles Dickens-style be transported to 2033, we would maybe not recognize our central city,” Cap Metro president and CEO Dottie Watkins said.

“If we could blink our eyes and Charles Dickens-style be transported to 2033, we would maybe not recognize our central city.” – Cap Metro president and CEO Dottie Watkins

Indeed, that change is likely to come because of the billions of dollars flowing into Project Connect and the I-35 expansion. But that’s not all. The jury is still out on driverless cars. Will they become ubiquitous? Walking and biking on many of Austin’s major roads is far from pleasant. How might the mobility bonds approved in 2012, 2016, 2018, and 2020 change that? Trains to nearby Texas cities are almost nonexistent. Could Austin get in on a high-speed rail network connecting the city to San Antonio, Dallas, and Houston?

With these questions in mind, the Chronicle asked 12 transportation officials, mobility advocates, and industry leaders to look into their crystal balls and discuss what it might look like to get around in Austin in 2033. In the words of Charles Dickens, “Ghost of the future … will you not speak to me?”

To Car …

With 10 years of construction scheduled to begin in mid-2024, the $4.5 billion I-35 Capital Express Central project won’t technically be finished by 2033 (prepare for lots of construction, folks). In fact, Austin City Council approved a resolution in October calling on a delay to the project until regional and city climate plans are finalized (prepare for lots of resistance, folks). The project aims to widen the highway to create more lanes for carpool and buses, not single-occupancy vehicles, according to Tucker Ferguson, TxDOT’s district engineer in Austin.

Ferguson said the project will improve transportation modes in Austin, from electric vehicles (charging stations) to biking to transit. One thing that all can agree on is that trying to bike or walk along the I-35 frontage roads is scary. Once the three I-35 projects (north, south, and central) are completed, someone would be able to use a continuous shared-use path for the 30-mile stretch. It also includes some widened bridges, which Ferguson said will have protections for people walking or biking.

However, the project is not exactly popular among Austinites. (The Austin Chronicle office is one of many highway-adjacent buildings slated for demolition should the project move forward.) Advocates and some city leaders have criticized the expansion for its lack of environmental considerations and the idea that widening the highway will induce demand. Urban planning experts argue that adding lanes to highways incentivizes developers to build farther out from the city’s core, which leads to more car travel and negates any congestion gains from widening the highway in the first place. As for environmental impacts, Council Member Chito Vela told the Chronicle the project will increase emissions by 50,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide per year.

“Induced demand, in my mind in the way that some use that term, sort of implies just because we built a roadway, people were going to start driving more, and I would submit to you that the demand is already there,” Ferguson said. Instead, he said TxDOT is simply responding to the demands of a growing city. But save Mayor Kirk Watson, it is hard to find many city leaders who favor the project.

“The state transportation department is drastically out of step with how the public feels,” Safe Streets Austin Board President Adam Greenfield said. He pointed out how dangerous TxDOT roads are – they account for the bulk of Austin’s road deaths – and noted that the public still has time to speak out against the expansion.

“The state transportation department is drastically out of step with how the public feels.” – Safe Streets Austin Board President Adam Greenfield

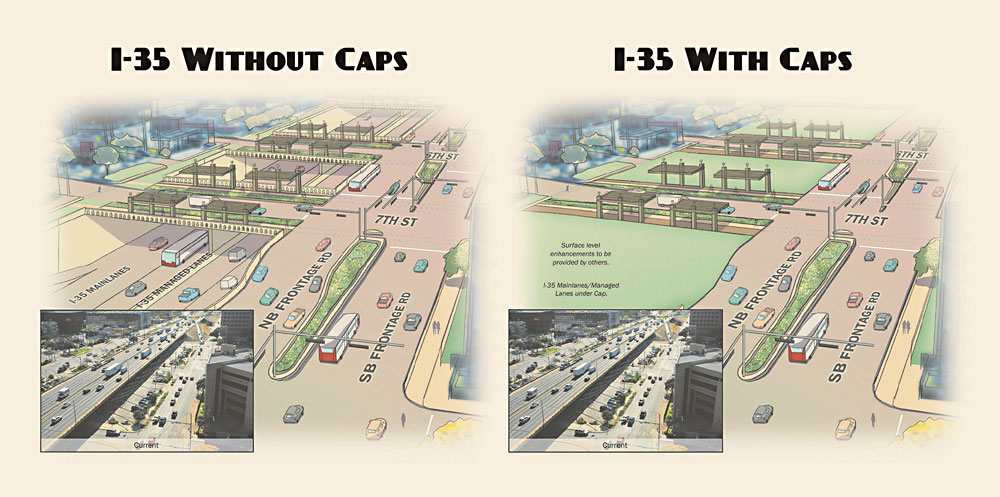

Another contentious aspect of the project has been discussion of caps and stitches – decks that would cover swaths of the highway. Those would likely happen in tandem with the expansion. “It’s going to be disruptive enough to do this construction, so it makes sense to build it at the same time,” Ferguson said.

Ferguson and TxDOT have been steadfast that they will design the I-35 project in a way that allows for the caps to be implemented, but they will not fund them (estimates put costs in the hundreds of millions). TxDOT says it will need to see cap funding secured by the end of 2024. The University of Texas announced interest in caps from Dean Keeton to 15th Street, and the city would be on the hook for other caps, possibly between Fourth and Sixth streets. Both see them as a way to provide options for cyclists and pedestrians who need to cross the behemoth highway.

… Or Not to Car

In fact, having options was a concept stressed by almost everyone interviewed for this article. Right now, those options don’t include much of a rail network (sorry, Red Line and solitary Amtrak train to San Antonio). Project Connect aims to change that. While the revamped, realistic light rail designs underwhelmed some Austinites in the spring and detractors continue to vex Project Connect by way of lawsuits and bills at the lege, officials say it is intended to be the beginning of a larger network that should be further developed 10 years from now.

Commuters will have access to reliable light rail that comes every 10 minutes by the early 2030s, according to Jennifer Pyne, the Austin Transit Partnership’s executive vice president of planning, community, and federal programs. On top of that, the Expo and Pleasant Valley MetroRapid lines, expected to complete in 2025, will be well established, adding to Cap Metro’s existing MetroRapid routes (the 801 and 803).

The larger rail network – the proposed Green Line, which would go east from the convention center and eventually north to Elgin – could come later. ATP also lists extensions in its current design, which include stretching the line from 38th up to North Lamar Transit Center at the north, from Oltorf to Stassney at the south, and from Yellow Jacket to the airport at the southeast. The massive project will also cause changes to the bus network. Watkins noted that the agency expects to be operating the new light rail in 10 years, but the agency will have a predominantly bus-based system for the “foreseeable future.”

UT’s Alex Karner, an expert on regional planning, worries that the approach thus far has focused too much on where the light rail will go and not who Cap Metro will serve. “I think there are these very real questions around, again, user experience that are being neglected and that should be at the top of mind,” Karner said. Cap Metro should invest more in more public transit ambassadors who can improve the experience for less seasoned public transit users and up the frequency of buses and trains, he added.

Greenfield sees the political winds pointing toward a better transportation future. Project Connect passed in 2020 after multiple failed rail votes, and a flurry of mobility bonds passed between 2012 and 2020. Those mobility bonds are an underrated factor in how mobility could change in the Austin area, as I-35, Project Connect, and autonomous vehicles soak up the spotlight. How would a ride on a bike lane or shared-use path all the way down the gnarly road that is Airport Boulevard be possible? The mobility bonds. In fact, those changes will become evident in the coming years on nine corridors, as all construction will be underway by 2024.

“In many cases, the ultimate goal is to have a bike lane, some trees, and a sidewalk,” said Anna Martin, assistant director of the Austin Transportation Department. The bonds will fund shared-use paths and pedestrian hybrid beacons – where pedestrians push a button at a crosswalk and a red light stops traffic for them – and reposition bus stops to be in safer locations.

The city also has a Vision Zero policy aimed at eliminating traffic deaths and serious injuries. The effort has yet to make significant gains. For example, the number of road deaths rose from 115 in 2021 to 118 in 2022. “What we feel the magic potion is, is to be able to safely provide folks with a safe alternative to driving,” said Richard Mendoza, the city’s director of public works. He added that working with autonomous vehicles could play a part. (Though that’s messy, too: Cruise has suspended its autonomous vehicle operations in Austin, after a federal investigation into their operations in San Francisco.)

The Barton Springs Road safety pilot offers one window into how roads might look safer in 10 years. The pilot included reducing the car traffic to one lane for a stretch and widening the bike lanes. Martin said the initial results from the project have been promising. “We have a back-pocket list of other projects we’d like to take on. There’ll have to be public outreach and public practices associated with that, so I don’t want to name any street, but I think Barton Springs Road has really proven that it’s possible.”

However, most of Austin’s traffic deaths happen on TxDOT roads that tend to be higher speed. Ferguson said TxDOT will improve safety through its “three Es” approach – engineering, education, and enforcement. Engineering improvements range from improving guardrails to adding rumble strips. He also sees technology in autonomous and connected vehicles as a key to improving safety. The state agency is incorporating fibers on some of its local projects that will enable vehicles to better communicate on the road.

In terms of enforcement, Karner doesn’t think current policing is working. He said enforcement priorities need to be reoriented, noting that ticketing “jaywalkers” is not an effective way of making streets safer and disproportionately impacts people of color. Enforcement should focus on dangerous driving, like running red lights and speeding.

Trains!

Travel for Austinites isn’t limited to commuting within Austin. Consider a current trip to Houston and options are scant. Drive a little under three hours, take a bus in a little over three hours, or take the less-than-one-hour flight (don’t forget to factor in the headache of airport travel). One missing option: trains.

In recent months, a coalition has set out to change that by reviving seemingly dead intercity rail plans and forging new ones. Travis County Judge Andy Brown has been at the forefront of those conversations. The once dead Lone Star Rail District would use Union Pacific rail lines to connect suburbs like Georgetown, Round Rock, and New Braunfels to Austin and San Antonio.

An Amtrak train, like County Judge Andy Brown would like to see connecting Austin, Dallas, and Houston (Photo by Getty Images)

“It makes me sad that with all this money pouring into I-35, nobody decided to put a train down the middle of it.” – Travis County Judge Andy Brown

Clay Anderson, the executive director of Restart Lone Star Rail District, was not yet born when the effort kicked off in 1997. It fell apart in 2016 after years of planning when Union Pacific pulled out. However, Anderson said that Union Pacific is not the bad guy. Instead, regional officials failed to inform the massive rail company of their planned passenger rail schedule and frequency. He also thinks the plan needed political champions.

Indeed, regional transportation is top of mind for Cap Metro, too, as Watkins pointed to productive conversations with Leander Mayor Christine DeLisle around Cap Metro services in the Austin suburb. With the Tesla “Gigafactory” east and the coming Samsung factory north, there will be heightened urgency for mobility options outside of the city’s core.

With that in mind, Anderson is making his proposal specific, outlining 19 stations for the regional line, investing in new tracks that could help Union Pacific add capacity, and detailing its impact on Austin-San Antonio car traffic. A Columbia University researcher determined that fast, efficient rail between San Antonio and Austin could carry about 4 million people per year – roughly 20% of yearly travel between the cities. But the timeline is TBD, as a study still needs to be done to determine station costs and upgrade needs to the existing rail.

The Texas Central project represents the sexier train plan. The high-speed rail project is currently set to go from Houston to College Station to the Dallas/Fort Worth area. Brown would like to see that line extend from College Station to Austin to San Antonio (and eventually to Monterrey, Mexico). The train would reach speeds over 200 miles per hour – comparable to trains in Japan – meaning it could take about 90 minutes to get from Austin to Dallas/Fort Worth.

Advocates point to the project’s potential to improve safety outcomes for intercity commuters, reduce environmental impacts (the train would be electric), and reduce congestion on major highways like I-35. “It makes me sad that with all this money pouring into I-35, nobody decided to put a train down the middle of it,” Brown said. Unsurprisingly, he would like to see TxDOT foot some of the intercity rail bill.

Brown also said increased federal funding for Amtrak will allow more frequent trains between San Antonio and Austin. Currently there is one train per day, but that number could grow to five to 10 within five years. Despite the nascency of these projects, he is optimistic. “By 2033, we could be riding high-speed rail from Dallas to College Station to Austin,” Brown said. “I think that is within the realm of possibilities.”

Too Much Tech?

For those who want to get to Houston, but don’t want to put their hands on the steering wheel, autonomous vehicles could offer another alternative. “Within 10 years I would love to find intercity, interstate travel with autonomous vehicles,” Cruise’s Austin General Manager Michael Staples said.

Austinites have not necessarily felt inclined to welcome the AVs, as they have at times seemed to struggle to navigate crosswalks and bike lanes and have caused issues for emergency vehicles. In fact, a Chronicle editor noted that during Austin’s August Pride Parade, Cruise seemed to draw the loudest boos of the many corporations that showed up to the event. Now, the company has paused operations in Austin to “rebuild public trust.”

While city and public transit officials’ views on the vehicles ranged from wait-and-see to downright skepticism, Cruise and Waymo (an Alphabet subsidiary formerly known as the Google Self-Driving Car Project) are confident that their vehicles will radically change how Austinites get around. They tout their technology’s ability to improve safety and provide accessible transportation. Staples likens the transition to Uber and Lyft a decade ago. What once seemed foreign and perhaps even scary – getting in a stranger’s car for a ride – is now the norm. “Eight years later, and everybody Ubers. ‘Uber’ is a verb.”

Waymo’s Chris Bonelli sees a world where someone could take one of its vehicles from Austin to one of the neighboring Texas cities, but the company’s current priority is ride-hail service. He said the company wants to eventually provide a service that covers “the vast majority of Austin.” The goal for Cruise is to expand its footprint in the city and eventually reach places like Round Rock and San Marcos.

What else could change by 2033? Both companies’ autonomous vehicles in Austin are currently at Level 4 autonomy, meaning there is a person in a control room ready to help the “driver” navigate a tricky situation. In 10 years, Bonelli estimates, Waymo’s vehicles will be Level 5, where the person in the control room is no longer necessary.

How the technology integrates with non-car travel is also still a question. “We connect people to the transit system. They have an aboveground light rail kind of system,” Bonelli said of Phoenix, the city that Waymo is most advanced in. “Some people get from their house or their school or whatever to the train station to then go the rest of their way, so it can kind of complement transit and not just take over.” Staples also noted the role that AVs can play in the “last mile” conundrum, particularly helping folks get to bus stops and rail stations.

Watkins is an AV skeptic. She said bikes tend to work better for “last mile” travel because they take up less space on the road. However, she does see aspects of the technology coming to buses in the coming years, including lane-assist technology that could give a driver a nudge if they drift into a different lane. ATP is not banking on AVs to help people get to train stations. “Autonomous vehicles are cars,” Pyne said.

There are also initial hopes that AVs will improve road safety, which would create a transportation ecosystem more welcoming to pedestrians and cycling. No doubt road safety is sorely needed in a state that hasn’t seen a day without a death on its roads since Nov. 7, 2000. But city officials aren’t yet convinced. It’s too early in development to understand what impact the cars will have on road safety, Mendoza said.

Karner sees simpler safety fixes than this new technology. For example, intoxication and speed are two of the main causes of road deaths and injuries, so why not have Breathalyzers in our cars or lower speed limits?

“If we don’t get serious about providing housing options that are affordable and accessible, in places where walking, biking, and public transit use are realistic options for folks, then things are gonna look the same and probably they’re gonna look worse.” – UT professor Alex Karner

Transportation Isn’t All Transportation

One of the perks of autonomous vehicles is having the freedom to do as you please while the car drives. However, some have expressed concerns about what AVs mean for the future of land use in Austin. Currently, the city lacks the density necessary to shift reliance away from cars. If someone can sit in a car they don’t have to drive during rush hour, would it encourage more folks to move farther out from the city?

Staples doesn’t necessarily see that as a bad thing, while noting that he’s not a land use expert. “I think having more of a sprawling thing where people can find … reasonable places to live across the market and not have to travel an hour and a half – I think that could actually be good.”

The worst outcome in Watkins’ eyes is zero-occupancy vehicles. “Imagine zero people in a vehicle because that vehicle’s driving itself around to do something, to take somebody to deliver lunch, or to go pick somebody up, and they just drop somebody off and now they’re gonna go pick somebody else up but for some period of time they’re not carrying anybody,” she said. “That just feels like a headache we don’t need, quite frankly.”

Most agree that housing is a vital player in the transportation landscape. “If we don’t get serious about providing housing options that are affordable and accessible, in places where walking, biking, and public transit use are realistic options for folks, then things are gonna look the same and probably they’re gonna look worse,” Karner said.

In particular, dense, affordable housing enables a more efficient public transit system. “Transportation policy is all about moving people and how do we get people from where they are to where they need to go,” Watkins said. “How do we move somebody from point A to point B and then point B to point C? And the further apart points A, B, and C are, the harder that is to accomplish.” Pyne said placing rail lines closer to development boosts ridership and makes ATP more competitive for federal grants.

Despite promising solutions to our transportation problems, Austinites are used to big ideas that sometimes disappoint – the light rail, for example, was scaled down because of cost and won’t reach many core users north and south of Downtown. Austin Justice Coalition’s João Paulo Connolly sees a lot of obstacles in the way of a bright future for Austin transportation, but still feels hopeful. “I believe we can change the pattern of our destiny collectively,” he said.

Indeed, some see the changes spurred by voters over the past decade as indicative of how political will can change in Austin. If that political force continues to embrace a transportation ecosystem that lends itself to more options on the road, then maybe that “ghost of the future” won’t be so scary after all.

Got something to say? The Chronicle welcomes opinion pieces on any topic from the community. Submit yours now at austinchronicle.com/opinion.